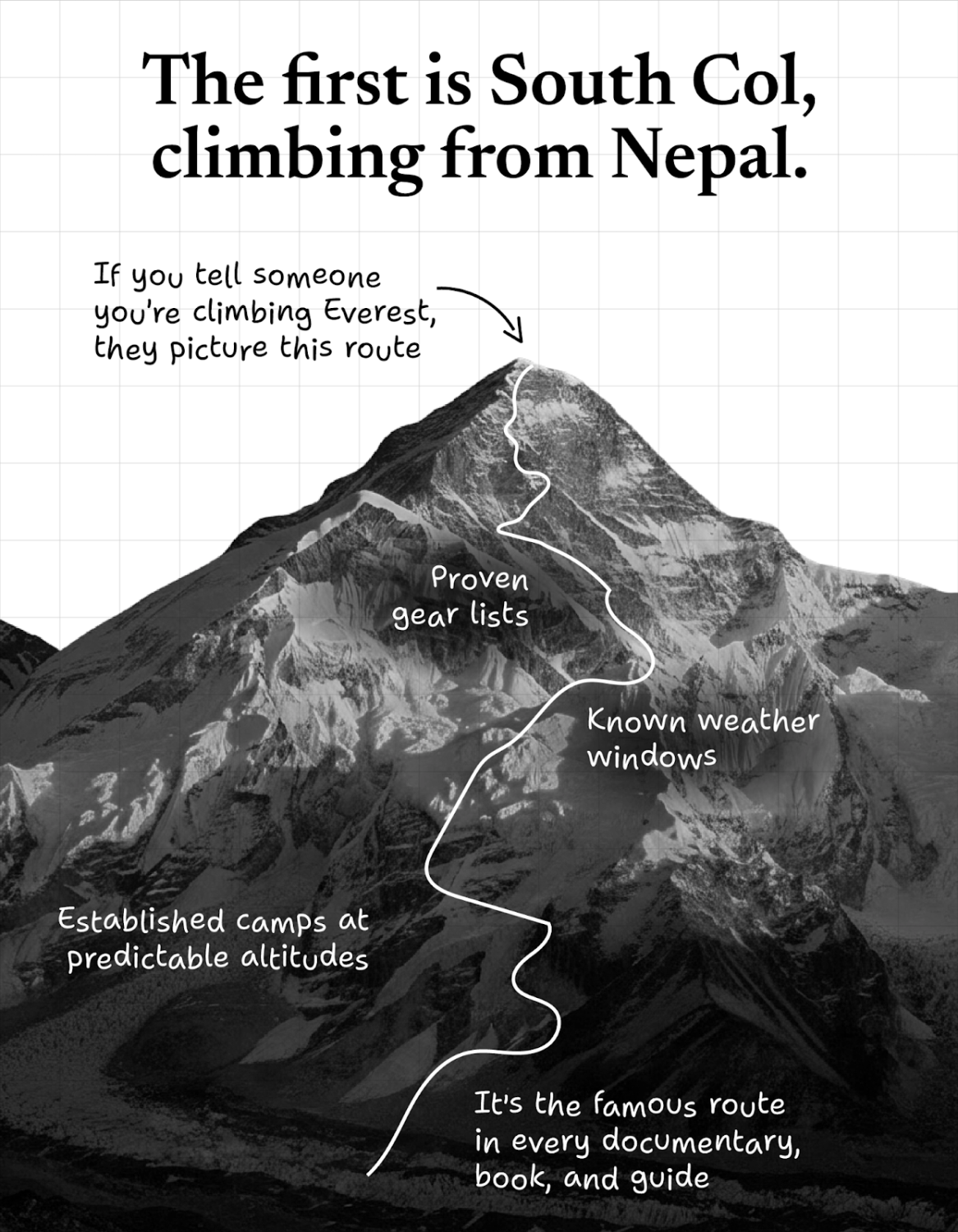

Everest has two routes to the summit.

Same destination but with different camps, different oxygen requirements, and different success rates.

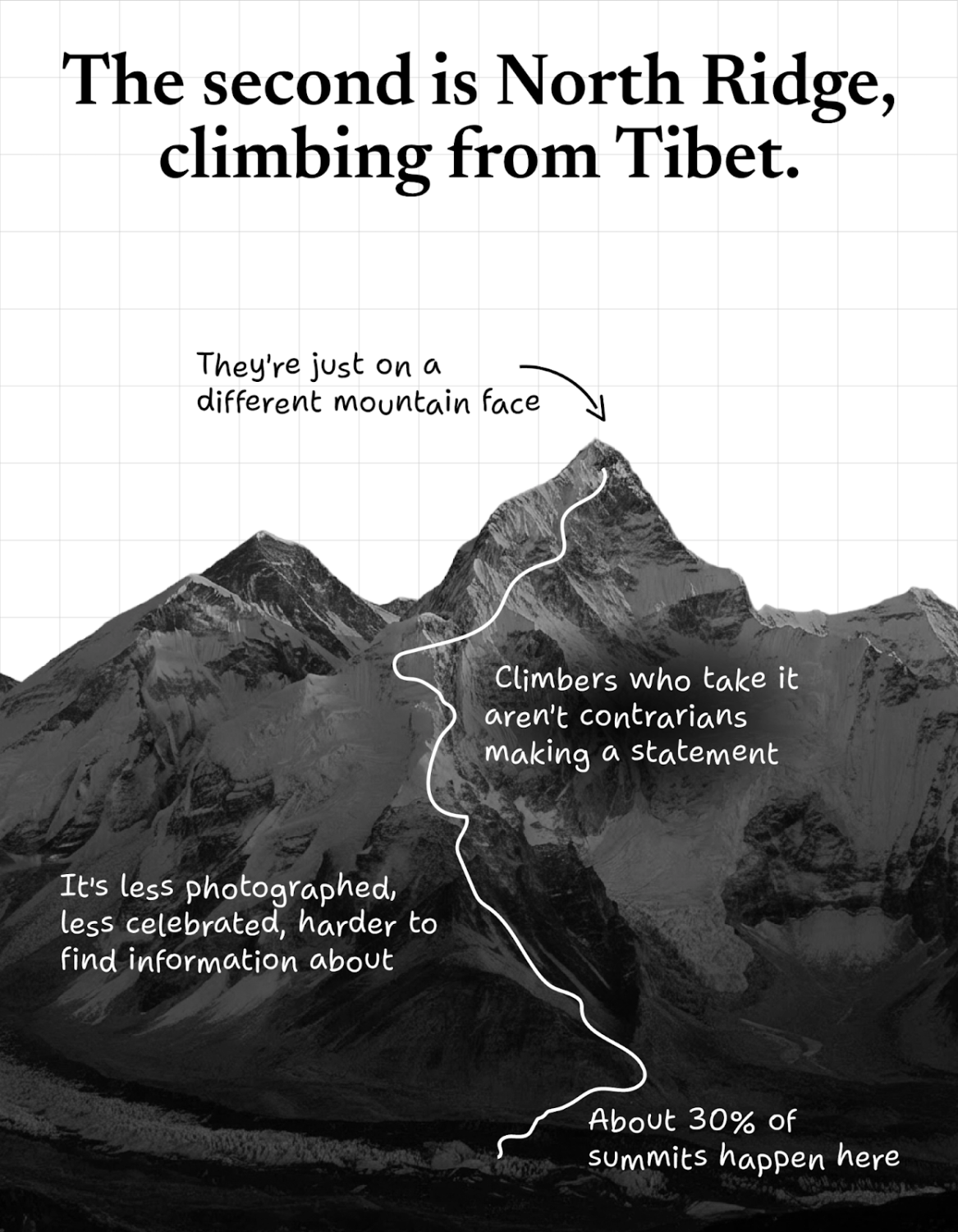

No one calls North Ridge ‘the future of climbing.’ It's not competing with South Col. It's just there, a parallel.

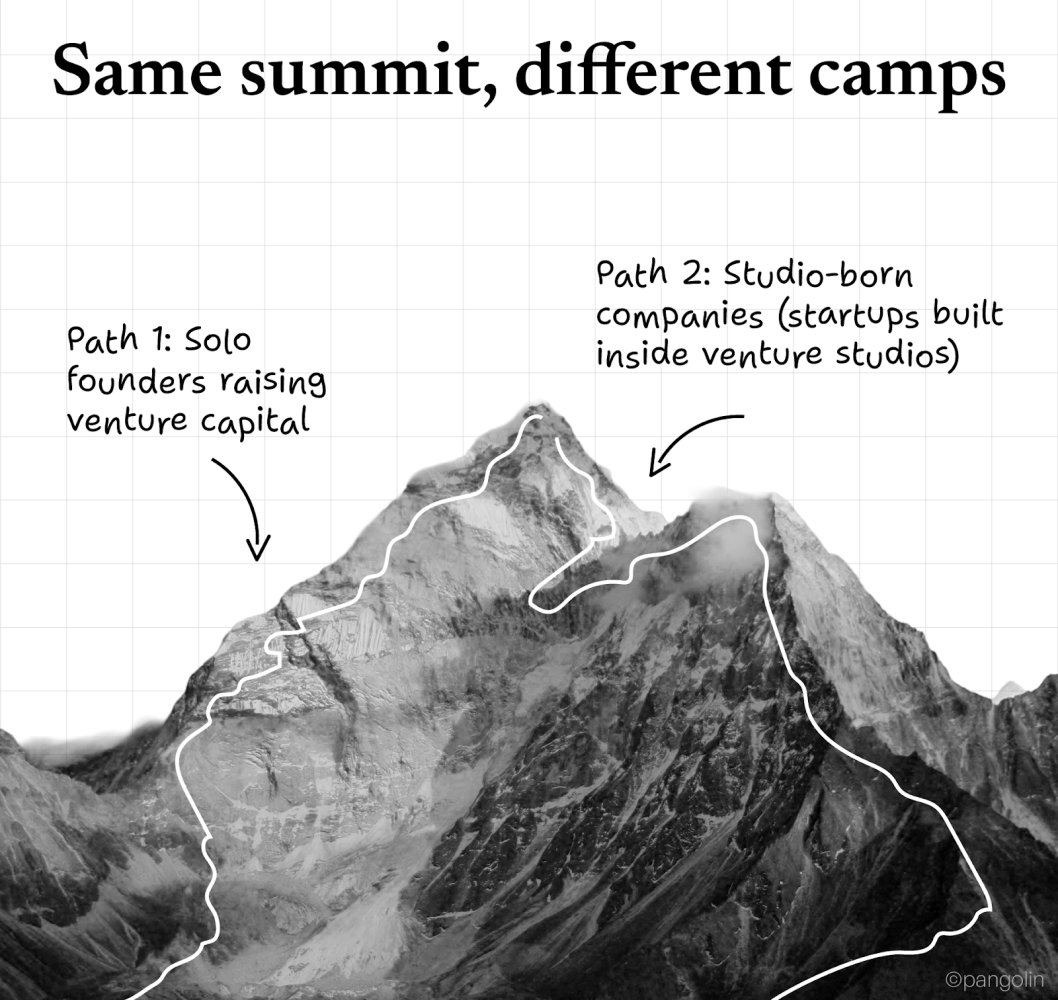

Something similar is happening in venture building.

There's the path everyone knows where solo founders raise venture capital, burn through seed rounds, and race to Series A. Every accelerator teaches this, every podcast discusses it, and every founder studies it.

But there's a second path that's been quietly working where studio-born companies, often funded with Revenue-Based Financing instead of traditional VC, are reaching the same milestones faster and with higher success rates.

Yet almost no one writes about it. No courses teach it and founders don't know it exists.

It's not the ‘future of venture.’ and it's not replacing anything, but it's just there working, parallel, unmapped.

And because it's unmapped, founders who might benefit from it don't know what the camps look like, what metrics matter, or when to choose one route over the other.

For fifty years, venture capital worked like wildcat oil drilling in the 1920s.

You'd stake hundreds of prospectors (optimistic founders with rough maps and boundless energy) and send them into the wilderness. Most wells came up dry with most being zeros written off in quarterly reports. That was expected.

But the model worked because of the gusher: the rare strike so massive it paid for a thousand failures. Facebook, Google, Uber, this became Silicon Valley's governing theology. Accept chaotic, high-volume failure as the price of infinite upside.

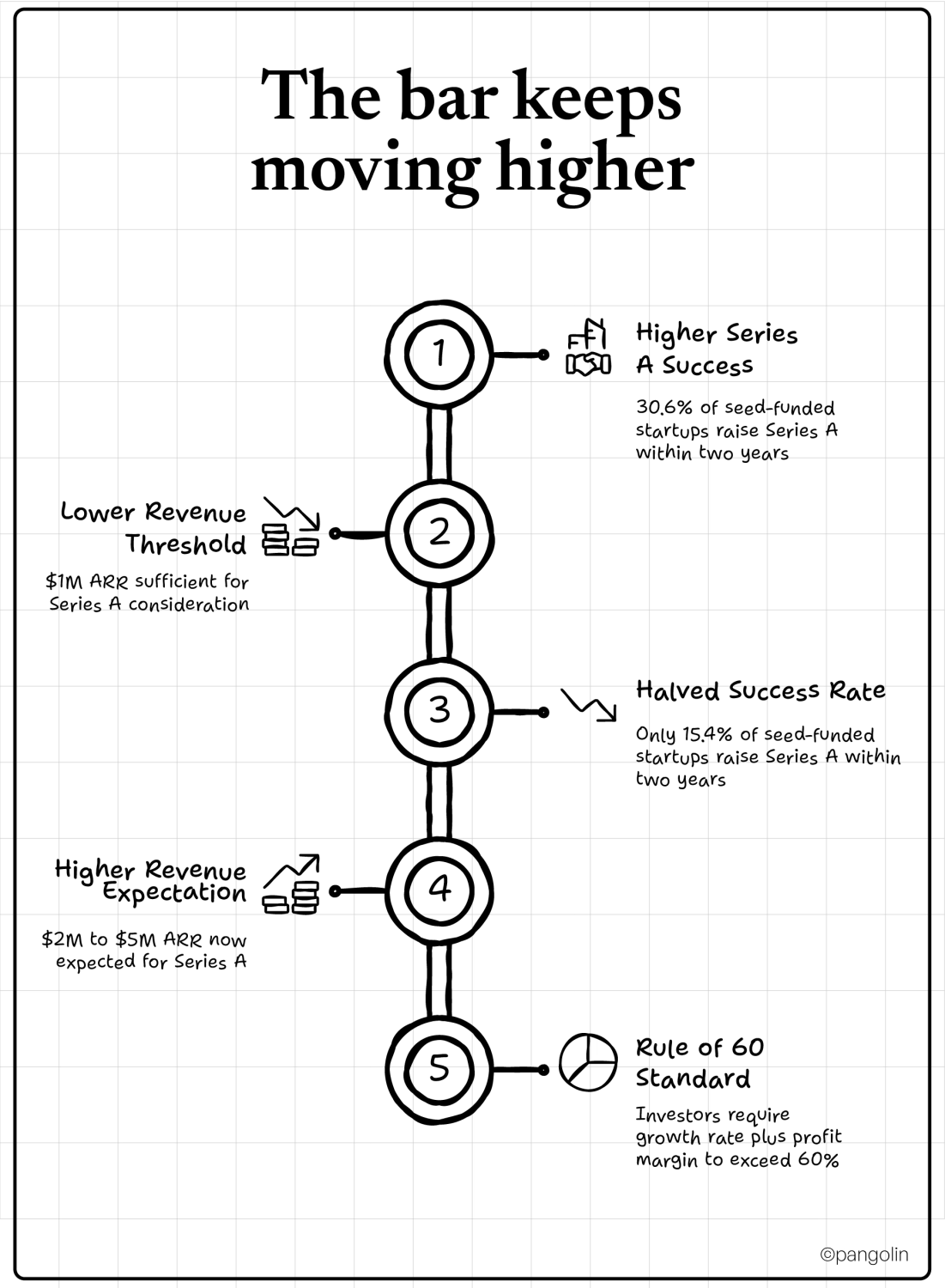

Then the math stopped working.

Customer acquisition costs skyrocketed and what cost $10 per customer in 2015 now costs $50 or more. Talent got more expensive while capital markets, disciplined by higher interest rates, stopped tolerating ‘efficient waste.’

You can build a great product, find real customers, hire talented people, execute well and still have less than a coin-flip chance of raising your next round.

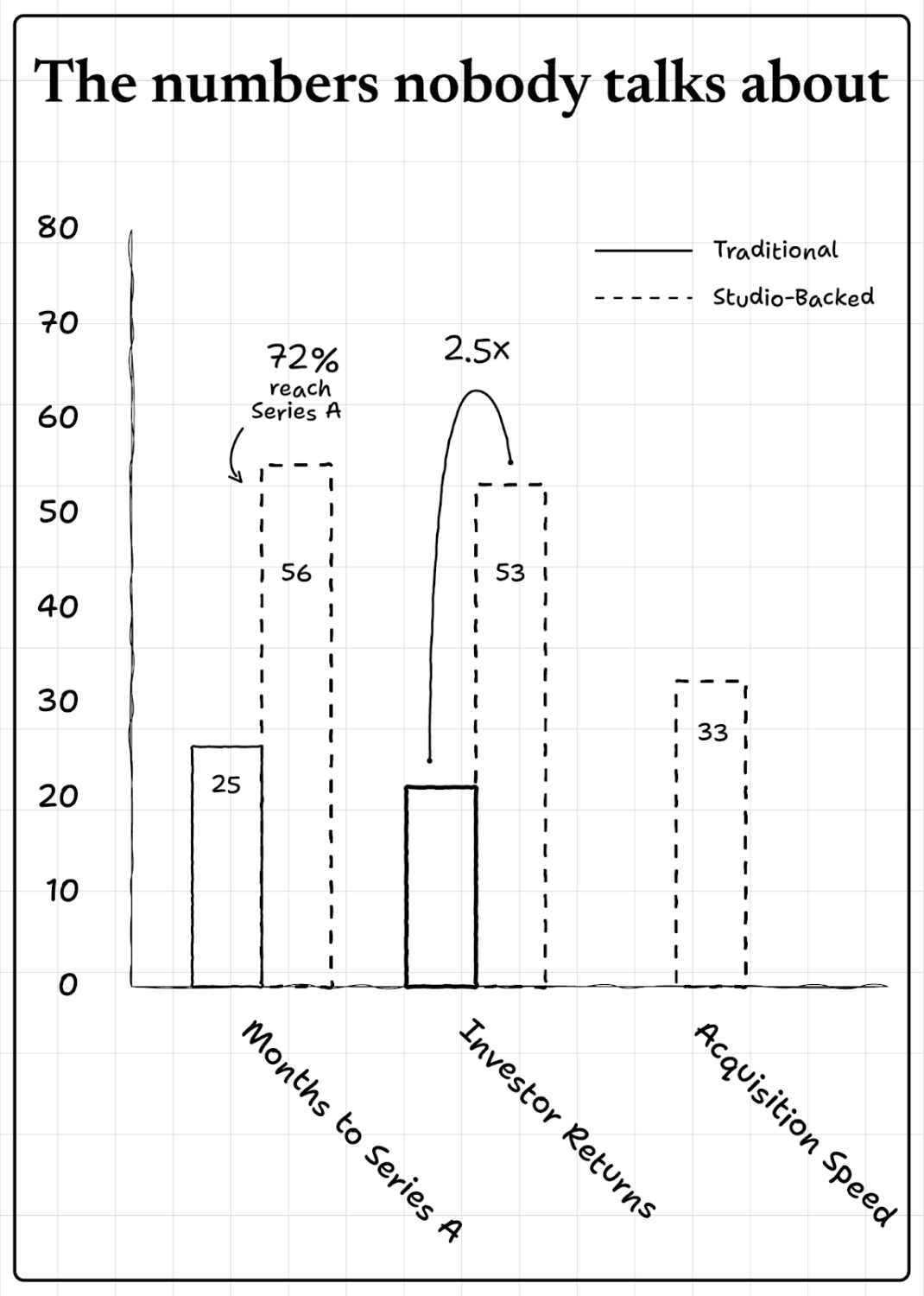

Meanwhile, studio-backed companies show a different pattern:

This isn't anecdotal. The Revenue-Based Financing market (which many of these companies use) is growing from $6.4 billion (2023) to a projected $178 billion by 2033.

Why? The market is unbundling.

For decades, venture capital was a bundled product: capital, advice, network, governance, operational support all in one package. The problem? A partner on 12 boards can't meaningfully recruit engineers for 12 companies. They can't build your financial model or debug your supply chain. They're spread too thin.

So the market is splitting:

Each does one thing well instead of everything poorly.

1. The vocabulary doesn't exist. We measure success in funding rounds and TechCrunch writes ‘Company raises $50M Series B.’ Revenue milestones and founder ownership percentages don't get headlines. No one writes: ‘Founder exits with 62% ownership in $85M acquisition.’

2. The infrastructure is fragmented. Studios and RBF providers aren't organized. No manifesto, demo Days, or shared playbook. They're just working.

3. Survivorship bias. Every unicorn gets documented. The $200M acquisition where the founder owned 58% and made $116M? Invisible even though that's more than most late-stage founders make after four rounds of dilution.

Studios test ideas in 100 days for $25K to $50K with customer interviews, fake MVPs, pricing tests.If it doesn't work, they kill it at Day 90 after screening 200 to 300 ideas to launch just 2 or 3.

Traditional path? You raise $2M, spend 18 months, then discover the market doesn't want it. Failure costs 40x to 80x more.

What you give up: The freedom to ‘figure it out as you go.’ Studios require proof fast and not every idea fits that constraint.

Solo founders spend months setting up payroll, legal structures, recruiting pipelines. You're building the company and the infrastructure simultaneously.

Studio founders plug into existing systems with legal templates, HR, shared engineering teams, and vendor relationships where everything's ready so you can focus on customers and product.

This is why studio companies reach Series A in 25 months vs. 56.

What you give up: 30% to 60% equity at Day Zero. But studios use ‘Super Pro-Rata’ clauses (if their stake blocks future fundraising, they dilute themselves). You're playing a 72% probability game, not 42%.

Once you hit $50K to $100K MRR, you unlock Revenue-Based Financing. Borrow $500K, repay $750K (1.5x) at 5% of monthly revenue. No dilution or board seat.

Traditional founders use equity for everything. By Series C, they own 8% to 15%.

Studio founders save equity for real risks. They use RBF for predictable growth and at exit, they own 40% to 60%.

What you give up: RBF requires operational discipline from day one. You can't access it without proven unit economics.

The funding model is the culture model where what you optimize for shapes who you become.

Traditional path: Speed, external validation, swing for unicorns. Parallel path: Probability, operational rigor, founder ownership.

The question isn't which is better. It's which trade-offs fit what you're building.

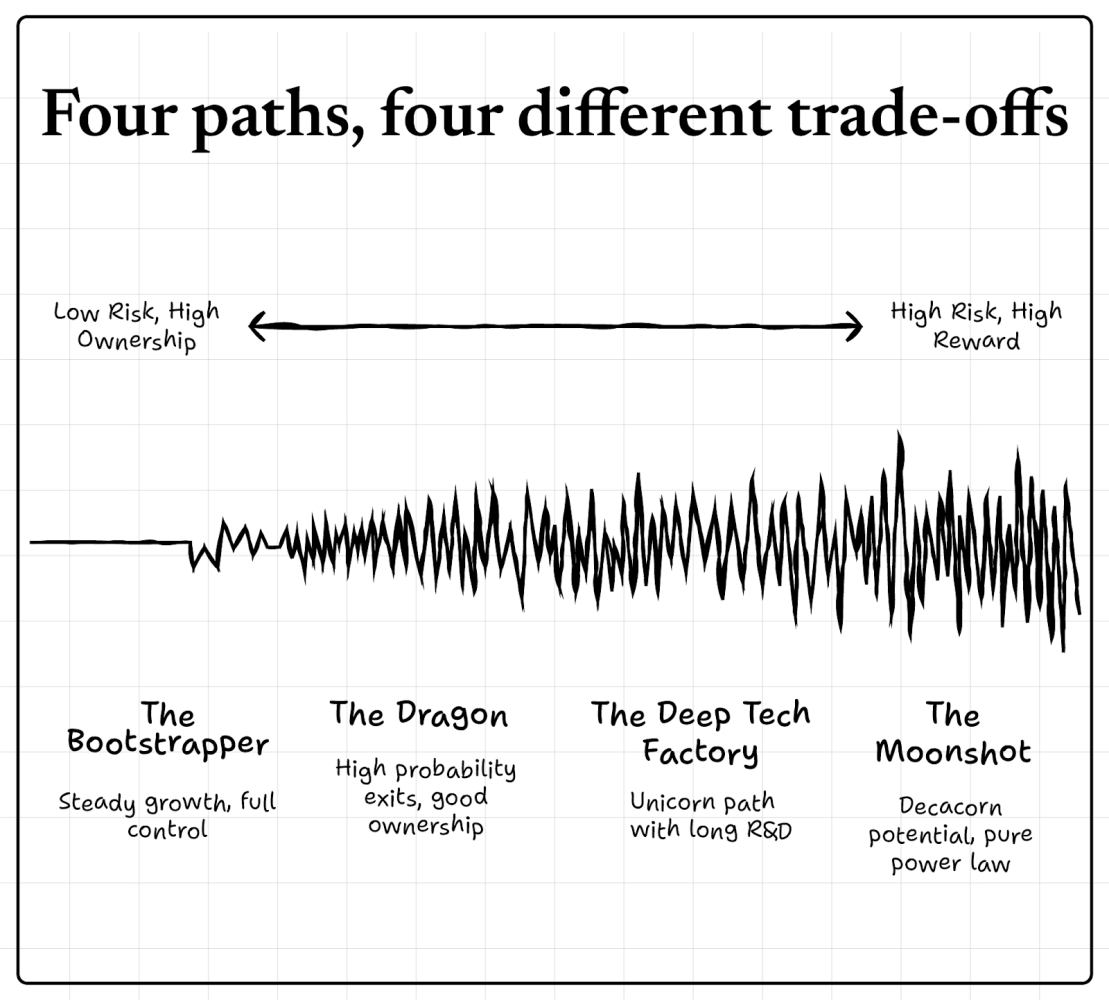

There isn't one right path. There are four.

Think of it as a 2x2 matrix. One axis is how you fund (VC for R&D risk vs. RBF for proven models). The other is how you build (studio-partnered vs. solo-independent).

The Dragon (Studio + RBF): High-probability exits ($100-300M), 72% success rate, 40-60% founder ownership. Best for vertical SaaS, D2C, marketplaces.

The Deep Tech Factory (Studio + VC): Industrialized R&D for biotech, AI, quantum computing. Reliable path to unicorns when you need years of R&D before revenue.

The Moonshot (Solo + VC): Category creation. SpaceX, OpenAI. Decacorn or zero. Pure Power Law.

The Bootstrapper (Solo + Revenue): 100% ownership, lifestyle freedom. Mailchimp's $12B exit with zero outside capital.

All four are legitimate depending on what you're building and what you value.

[Download: The Venture Precision Matrix]

The traditional VC path still works where Series A exists and unicorns still matter to some founders.

What's new is the vocabulary. For the first time, there's language for a path that was working but invisible. Founders now have leverage: ‘We can build with a studio or raise a traditional seed which gives us better terms?’

Success metrics have also shifted where top-line growth matters less than retention, blitzscaling is out, capital efficiency is in, and $1B valuations matter less than $100M exits where the founder owns a meaningful piece.

We're moving from ‘one way to build’ to ‘two legitimate paths with different trade-offs.’

Everest's North Ridge isn't the ‘future of mountaineering.’

It's just a different route. Some climbers take it because South Col has become harder (15.4% Series A success rate vs. 30.6% four years ago). Some take it because the timeline fits better (25 months vs. 56). Some because they value a 72% probability over 42%. The wildcatting era optimized for chaos and gushers.

The factory era optimizes for industrialized creation: killing bad ideas for $25K instead of $2M, screening 300 ideas to find 3 winners, delivering exits 33% faster.

None of that makes it better or worse. It makes it parallel for founders who value ownership over headlines.

Probability over variance. Dragons over unicorns.

[Download: The Venture Precision Matrix]