Welcome back to the 5th edition of The MOAT. This time I will be talking about something I have seen first-hand and consider an essential skill in any organization running smoothly.

Let's get into it.

I'm writing this from my balcony in Kochi, watching a pair of sunbirds fight over the hibiscus flowers in my garden. They've been at it for twenty minutes. Tiny, fierce little things, completely convinced their way is the only way.

Reminds me of most leadership meetings I've sat through.

If you're new here, welcome to The Moat. This is where I work through the messy stuff about building Pangolin. The mistakes. The patterns I keep seeing. The things that cost real money before I figured them out.

A leader's main job (like, the actual work) is getting work done through other people. Not doing it yourself. Getting it done.

Which means the single most important skill you have is giving a brief that actually works.

Not vision. Not charisma. Not strategic thinking. Those matter, sure. But if you can't brief someone so they know what to do? You're stuck. You can't scale. You become the bottleneck.

The higher you go, the more this matters. You're not doing the work anymore. You're enabling other people to do it. If your briefing system is broken, nothing else scales.

Last week I watched this play out in real time. Smart founder. Raised a Series A. Built something genuinely disruptive. Gave their designer a fifteen-minute audio brief. No written doc. No examples. No clear picture of what done looks like.

Two weeks later, the work comes back. Completely wrong.

And the founder's frustrated. Designer's frustrated. Everyone's frustrated.

But nobody's asking the obvious question: was that actually a brief?

A brief is not you describing what you see in your head.

It's not a statement of fact. Like, "We have an event coming up and we need collateral for it." Okay, cool. That's not a brief. That's just... a fact.

It's not telling someone what NOT to do without explaining why. I see this all the time. "Don't use that photo." Okay, but why not? What's wrong with it? How is that person supposed to know what to do differently next time?

It's not assuming people know what you mean.

A brief is a transfer of context. It's giving someone enough information that they can make good decisions without you. That's it. That's the whole job.

At Pangolin, we have this rule: if work comes back wrong, we assume it's a problem with the brief first. Not the person's competence. Not their effort. The brief.

This mindset shift matters. Because it puts accountability where it actually belongs, with whoever's doing the briefing.

Real question. Think about the last year. How much work needed to get done? How many briefs did you give?

Now think about the ones that went sideways:

Bad briefs stack up. They compound like debt. One bad brief costs you a week. Ten bad briefs cost you a quarter. A year of bad briefs and you're wondering why execution is so expensive.

Most of us take shortcuts. We're busy. We assume people will figure it out. We give a quick verbal download and move on.

But here's something I almost never see leaders do: ask someone how they prefer to receive a brief.

Do they process better with written docs? Verbal walkthroughs? Visual references? A mix?

If you want to actually enable people, this is where it starts. Not picking your favorite format and forcing everyone to adapt. Asking.

There's actual science here.

Working memory, like your brain's ability to hold information, maxes out at about 4 to 7 things at once. George Miller figured this out in 1956 and it still holds.

When you give someone a long, rambling verbal brief with ten different threads, you're literally overloading their brain's processing capacity. They're not dumb. You're just pouring more than their brain can hold.

What happens is they use all their mental energy trying to decode what you meant instead of actually solving the problem you need solved. Psychologists call this "extraneous cognitive load." I just call it exhausting.

Here's the math that haunts me:

You're setting up a 91% failure rate before anyone even starts working.

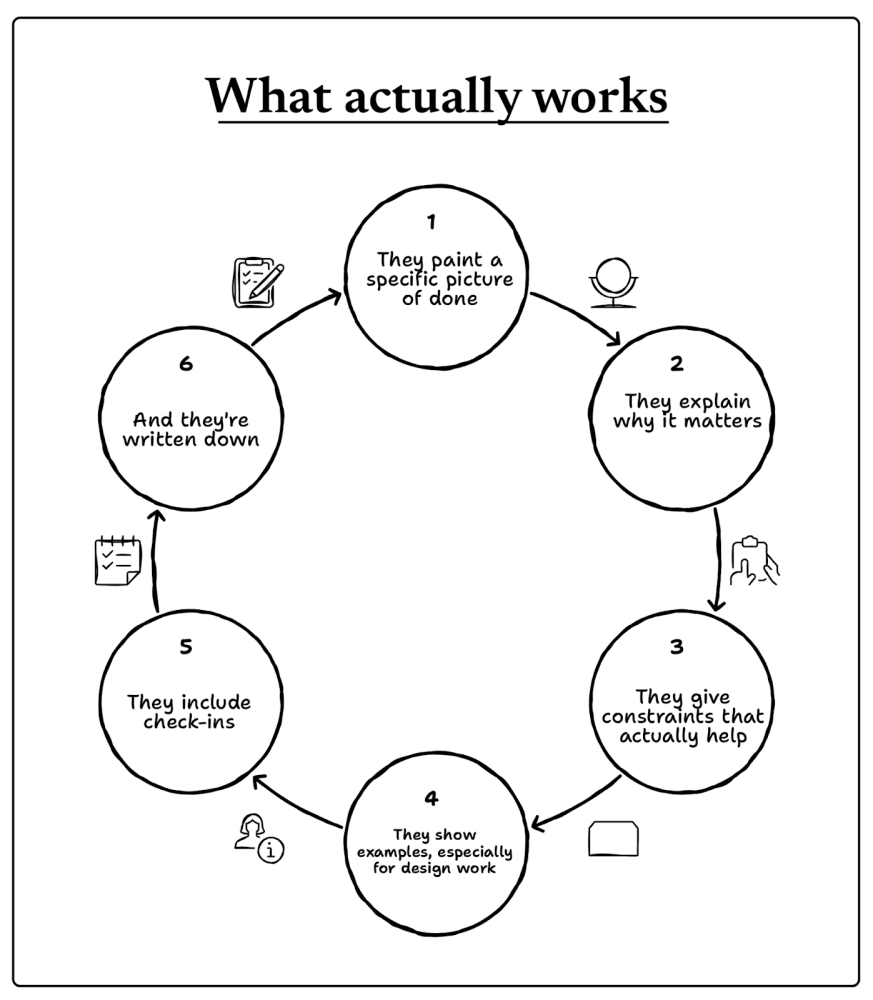

I've watched hundreds of briefs at this point. Client projects. Internal work. Agency handoffs. The ones that work follow the same pattern.

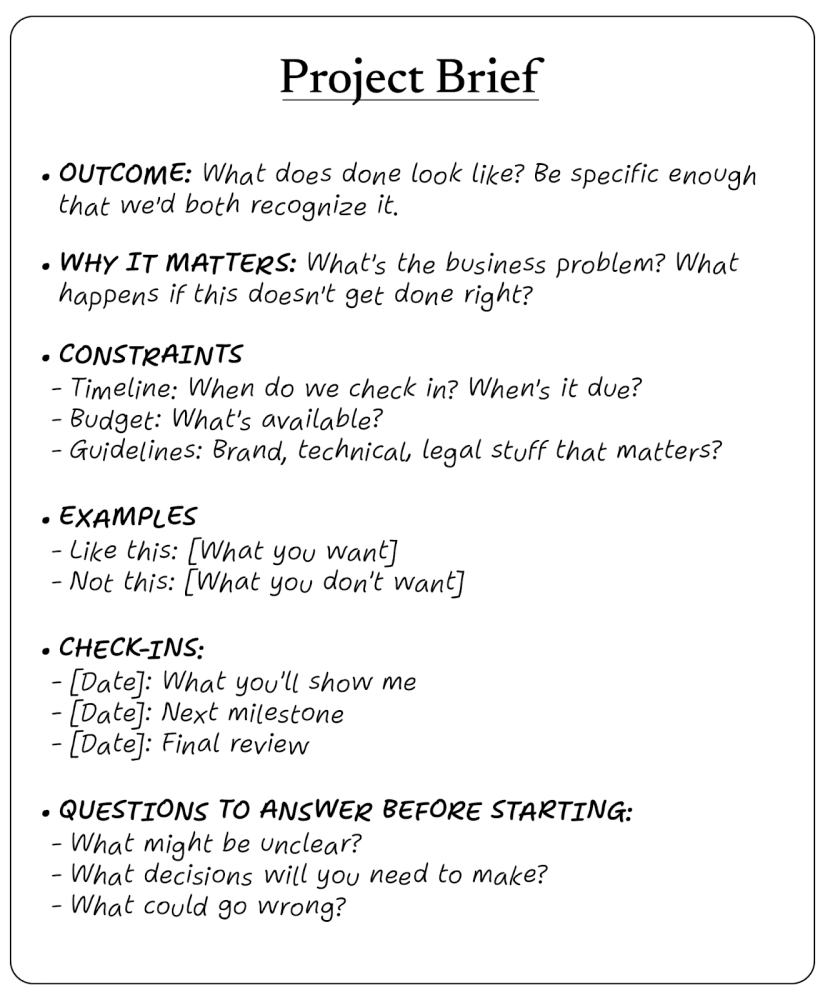

Not "improve the website." That's vague. Done is: "Reduce bounce rate from 65% to 45% by redesigning the homepage hero section with customer testimonials and a 30-second explainer video above the fold."

See the difference? One is a direction. The other is a destination you can see.

Context changes everything. "We need to update our positioning" is a task. "Competitors are launching AI features next quarter and we're about to look outdated. We need messaging that positions us as the only solution built for regulated industries" is a business problem you're solving together.

When people know the why, they make smarter decisions.

This feels counterintuitive, but constraints make work better. "Design something modern" is paralyzing. There are infinite ways to be modern.

"Design within our existing Webflow template using these three brand colors, max three custom illustrations, deliverable in Figma by Friday at 5 PM" is freeing. Now they can focus on solving the problem instead of wondering what you meant.

This is non-negotiable if you're briefing anything visual. Don't assume. Show what you want. Show what you don't want.

"Make it conversational" means nothing. "Tone like Drift's blog, casual but credible. NOT like HubSpot Academy, which feels too instructional. Here's a link, notice how they use short paragraphs and rhetorical questions" means everything.

Nobody should disappear for three weeks and come back with finished work. That's not trust. That's risk.

"Let me know when it's done" becomes "Tuesday at 2: show me three layout options with your reasoning. Thursday at 10: let's review the direction you picked with copy in place. Monday at 3: final review before we go live."

Milestones catch problems early. That's the whole point.

Always. Even if it's ugly bullets in Slack. Verbal briefs are where understanding goes to die.

You're busy. I'm not asking you to overhaul everything by Friday.

But try these three things:

1. Write it down. Even rough bullets. Take five minutes after your verbal brief and send a follow-up. Just doing this will cut your revision cycles in half.

2. Ask them to describe success back to you. Before they leave the meeting. You'll catch misalignments right there instead of three weeks later when they've built the wrong thing.

3. Ask how they prefer to be briefed. Seriously. Just ask. Some people need written docs. Some need to talk it through. Some need visuals. Adapt to them, not the other way around.

This is what I use for every project handoff at Pangolin now. Copy it. Change it. Make it yours. The specific format matters way less than the discipline of actually filling it out.

We've all given terrible briefs. I definitely have. The question isn't whether you've done it. It's whether you're going to keep doing it.

What's your worst brief story? I'd actually love to hear it. Drop it in the comments.

Until next month, Avani

P.S. - If you're trying to turn marketing chaos into something that actually works, that's what we do at Pangolin.